Mohammad Mehdi Tabataba’i brought the “Nameless” collection to Tarrahan Azad (Freelance Designers) Gallery in December 2012. The collection, though semiotically in line with the artist’s previous collections, stylistically announced his entry into a more realistic realm.

The works in this exhibition are divided into two categories: three works by the artist from his previous collection titled “You Were Busy Dying” and the rest of the works in the recent Nameless collection. As it implies “You Were Busy Dying” is the story of internal decadence, the routine life, the decline and downfall of human beings who are shown fading away and are close to decline and oblivion in a gray background with thin colors and a special design, while there is a fresh and flashy rose in the foreground plan which covers part of the body and mostly lips, therefore it creates a clear paradox between “being” and “pretending” or “what we are” and “what we pretend.”

In these works, the artist has incorporated photography techniques into painting, exactly like the time a photographer focuses on a subject and the background stage is pushed into the depth of oblivion and ambiguity and by doing so successfully depicts content within the framework of form as well as the relevant and meaningful technique.

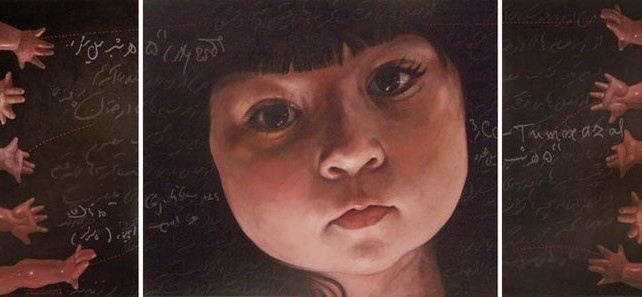

However, the Nameless collection hardly yields to decoding and reading the coding of this collection is to a great extent tied to the familiarity with the artist’s background and his works. The limbless and sometimes decapitated dolls of the previous collections show up in here as well, but they have become more three-dimensional, with bigger mass and so close to reality that they are horrifying, annoying, and pathetic. In one of the works, there are thirteen decapitated dolls on top of each other that you feel anytime they might slip on each other and jump out of the painting and fall just in front of you. From a realistic perspective and also the black background of the works, this collection seems to be a continuation of the “Ailments” collection in terms of content and form, which is an effective and creative narration of the artist’s personal life. The artist takes advantage of Triscupids in this collection as well and if the child was entangled in a mass of medical transcriptions and diets in that collection, the wooden horse is torn up into two halves in this one and masculine busts and other parent-like figures impose this restriction.

However, besides the familiar and repetitious element of doll or child which symbolizes doll, Tabataba’i intentionally and impassably puts the audience before an ambiguity. He writes in the statement for the exhibition: “… but when a collection gains name for itself, it imposes a specific reading on the audience which is influenced by the title of the collection and turns the audience into a partner for reading the artistic work, therefore the audience pays attention to the work under its title. That’s why this collection was named Nameless so the audience would not be obsessed with the name and have their own reading of the work without any presupposition.”

Even though works without any title are commonplace in naming artistic works, merely avoiding a title for works which are very general so they would act as a mirror for the audience or for works which are very abstract, like those by Pollock, in which titles are in practice imposition of a name for an unlimited general and endless implications, do not necessarily give the audience a free rein to dissect the meaning of the work.

We should accept that today artistic works are not merely paintings on the wall, but the statement, the title, the gallery’s atmosphere, lighting, decoration or even the criticisms on the work all lead to the formation of a work of art and, as each of them are engaged in demarcating the borders and determining the realms, they will not restrict the audience’s reading if they do not fall into over-revelation and superficiality.

Mahsa Farhadikia

Recent Comments