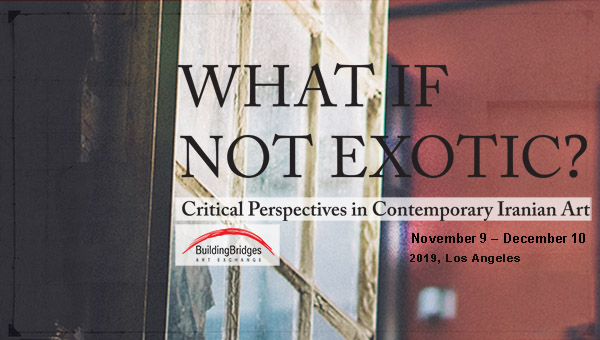

Curators’ Foreword

The idea for an exhibition titled What If Not Exotic? took form at a time when international art markets in general, and western art markets in particular, were filled with works of art that present predictable, marketable images based on cliché assumptions about the local lives, identities, and socio-political concerns of artists labeled as “Middle Eastern.”

For the past two decades, with the establishment of new art markets, many new brands with titles such as “Middle Eastern Contemporary Art” have begun to take shape. This general and inaccurate title, ignores the region’s varied history, art, and culture in order to present a reductive and homogeneous concept, suitable for market consumption. The subjects and symbols included in this type of “Neo-Orientalist” art are often like display windows that reflect the market’s demands: some of the main features it represent, include sociopolitical issues presented as repetitive slogans, the insertion of Orientalist elements, and the depiction of exotic spaces.

Due to its geography and the sociopolitical upheavals it has experienced in the decades following the Islamic Revolution of 1979, Iran is one of the countries that has been a suitable context for the formation of different variations of Neo-Orientalist art. For the last two decades, due to the shifting cultural policies, as well as the active role of private institutions, Iranian artists (particularly younger artists) have seen increasing opportunities to access to the region’s new markets and to present their work on the international scene. These shifts have had a significant impact in shaping this form of art; the type of art that sees itself from the problematically simplified perspective of the western viewer and his expectations, and therefore–intentionally or not–becomes distant from its intimate source material. Meanwhile, longstanding Orientalist projections of western viewers about this historic region, and its recent socio-political tensions and human rights concerns, raised the western viewer’s curiosity. Moreover, Curators, critics, and theorists have also played an important role in shaping the conversations that introduced this dubious artistic trend as the primary representation of contemporary Iranian art.

Inside many Iranian critical circles; however, this type of art is not simply valued because of its exhibition of political elements or symbols that indicate a “national identity”. Instead, art scholars have seriously criticized these works for their reductive and simplistic perspective. This is because, regardless of what the artists claim, the works do nothing to critique or question the status quo. Instead, by reducing a complex situation to a simplistic sentiment, they are ultimately further establishing the very means of reduction. This concern is at the heart of the exhibition What if Not Exotic? An in-depth exploration of contemporary Iranian art that bucks market expectations; featuring instead artworks that reflect the lived experiences of artists, and seeks to consider the varied and complex individuals, rather than the monolith of a singular brand titled “Contemporary Iranian Art”.

This exhibition is an attempt at presenting a realistic image of contemporary Iranian art–as an alternative to the common Neo-Orientalist representations of the “Middle Eastern” art in general and Iranian art in particular–in Western art markets. All the selected works maintain deep and significant connections to their sociopolitical context that fall beyond clichés and common expectations. In other words, they have not resorted to predictable and predetermined subject matters and visual elements to question their current political situation. In fact, these are pieces that have experiential aspects related to real limitations that artists face on a personal and professional level. Therefore, dialogue between these works and the artists’ lived context is a complex interwoven one that affects different aspects of the process: from the artists’ choice in media, to the size and the color palette, and from the style and formal language, to the subject matter. The exhibition is arranged in four main sections. In each section, a significant and emblematic aspect of Iranian art and life is examined: Public Spheres, Private Interiors,The Body; from defiance to deformation, and Memory; From Personal to Collective.

Public spheres refer to the places where individual desires and ruling order intersect. But in a public space where the expression of individuality as an active agent is reduced to the extreme, the experience of life is accompanied by a sense of alienation and passivity. This sense of bewilderment can be found in the present works both in subject matter and form, whether it is in their depiction of spaces in neutral colors or the angle of the camera. We selected works that go beyond a direct depiction of the contradictions between individuality and the prevailing rule of law, and instead show the bewilderment, alienation, and isolation of the individual in the public realm; a situation well described by Sohrab Sepehri the contemporary Iranian poet in his poem, “Us nil, us a look”.

When the public sphere becomes a space of control and surveillance, the private and interior spheres turns into a shelter where the individual can temporarily take refuge from social pressures. This form of escapism sometimes manifests itself in an obsessive attention to interior spaces in the form of still lifes and representations of human relations in the relatively safe confines of interiors. However, governing policies and social pressures are not only present in the public realm, but can easily bleed into the private space as well. Despite private spaces providing relatively safe havens where one can find refuge from ruling orders and experience the reprieve of intimate relations (such as Farzaneh Ghadianloo’s Thursdays series of photographs), even such spaces are not entirely free from the misery and irritations that exist in the public sphere. This fleeting privacy can indeed exacerbate one’s awareness of surveillance and control (such as Kathamandu series of photographs by Ali Nadjian and Ramyar Manouchehrzadeh).

Another way that contemporary artists practice escapism is by turning to a more personal past that has semi-universal elements. In these selected works the reference to the past is not achieved by inserting national-identity-related symbols (as is often the case in contemporary Neo-Orientalist works), but by using family photographs and personal artifacts as a means of memory akin to time travel, artists are allowed to explore their own lived experience even as it may unfold against a larger social backdrop.

The final group present in the current exhibition utilizes works that address the body as a means of experience. Here the body reacts to violence and isolation by becoming deformed and revealing physical attributes left by pain. Through technique and form, as well as elements representative of suppression, we are faced with the abject reality of a body that has been suppressed and tormented without any intermediary to comfort us. (Such as the human figure drawings of Shaya Shahrestani).

Although the present exhibition has no claims about being a complete all-encompassing representation of Iranian art, what it does claims to present is a more realistic version of a nation’s artistic dynamics where economic and political limitations can lead to a complicated, individualized, and extremely experiential effect on the works. Finally, if the juxtaposition of these pieces can present a meaningful alternative to the previous (and problematic) singular voice that has been heralded as “Contemporary Iranian Art”, then we can claim to have reached our objective of presenting multiple voices from among the complex phenomenon that is contemporary Iranian art.

Aria Eghbal – Mahsa Farhadikia

243 thoughts on “Curators’ Foreword”

Comments are closed.