Curated by: Mahsa Farhadikia, Mandy Palasik, Brandi Sjostrom, Naomi Stewart

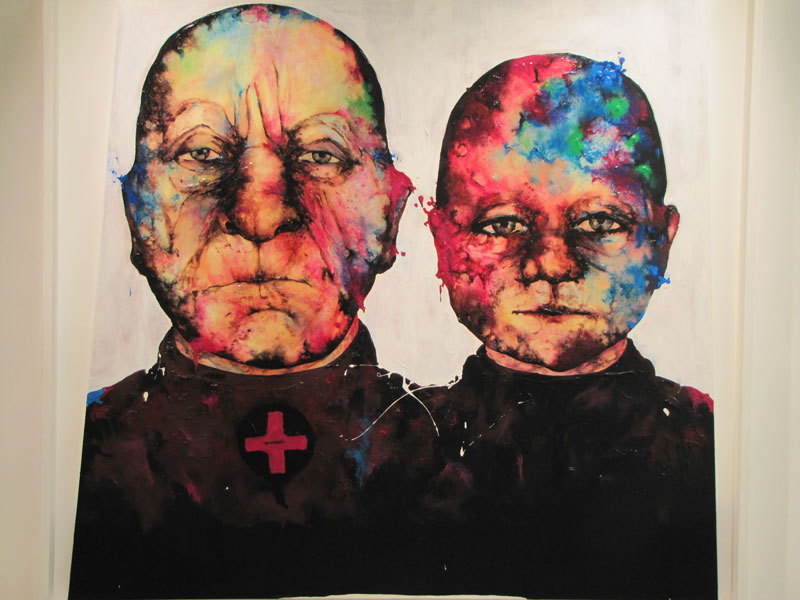

Artists: Janna Avner| Michael Chang|Evelyn Contreras|Christian Franzen|Richelle Gribble |Gottfried Haider|Julian Lombardi|Ariel Maldonado|Mandy Palasik|Allison Peck|Gazelle Samizay|Weng San Sit|Joshua Thomen

January 22 – March, 13 2021

Angels Gate Cultural Center

San Pedro, California

Hi everyone. Thank you all for joining us tonight. My name is Mahsa Farhadikia, an la-based independent curator, art critic and a member of AICA-USA. Tonight I am here as one of the co-curators of Borderline exhibition to discuss some of the main thematic frameworks of the exhibition. My pronouns are she/ her, and I am a woman with long blond hair wearing a black jacket and there is a green wall behind me. My curatorial interests include emerging and marginalized artists, contemporary art’s dilemmas, gender studies, post-colonial subjects and contemporary curatorial approaches. The introduction I am going to read to you tonight is an excerpt from an article I wrote for the exhibition catalog. You can find the main text in Borderline exhibition catalog available on Angles Gate Culatural Center Website.

Borderline exhibition starts with an ambiguous, playful metaphor. As inferred by its title, it plays with the references to a mental disorder of the same name, which as defined by psychologists occupies an in-between space in the spectrum of mental diseases. In its psychological definition, “The term borderline originally came into use when clinicians thought of the person as being on the border between having neuroses and psychosis, as people with a diagnosis of BPD experience elements of both.” Due to this definition, a borderline includes implications to an indeterminate and unsettled situation as well as to social categorization leading to hierarchization and stigma.

Borderline exhibition questions the notion of a borderline as it associates to the notion of categorization. Classification and categorization are among the tools humans have used throughout history to understand the world. Specifically, the exhibition questions the objective approaches dominant in the western logic and their efforts to put the world as the subject of knowledge “in order”.

The exhibition’s theme is based on challenging the certainty which is a result of drawing borders and defining categories both in social contexts and in ontological ones. On a social level, categorization has been used to put people in groups such as: “members”, “nonmember”, “insiders” and “outsiders.” As a result, drawing borders seems to be one of the most fundamental stages in the process of othering. Accordingly, what seems to be the harmless and even “rational” act of categorization has led to extreme demonization, xenophobia, homophobia, and other types of phobia. On an ontological level and inspired by scientific discoveries such as theory of relativity, the previously objective approaches toward categorization have been replaced by more subjective perspectives in contemporary thinking.

In view of such a major scientific revolution, other areas of knowledge, including philosophy and art, have undergone fundamental discursive shifts as well. Accordingly, we live in an era that has emerged from the ruins of certainty and absolute beliefs. Postmodern mistrust in the metanarratives of modernity such as rationality and progress, along with more traditional grand narratives, is born out of the ideas of relativity and uncertainty. As a result, the legitimacy of putting concepts, people, and objects into discrete categories is being fiercely questioned by the naturally existing chaos and disorder of the universe and its philosophical implications brought to the fore by contemporary discourse.

The idea of an exhibition titled Borderline is shaped out of this philosophical and socio-political necessity to explore the subjective nature of predefined categories by raising questions about the nature of a borderline as a determinative element in creating spheres of meaning. However, choosing such a theme might raise questions such as: why do we need to bring into attention the importance of the blurriness and constructedness of the borderlines, the overlapping of territories, and the eclectic nature of realities, if they already exist on various levels? The answer is that despite the paradigmatic shifts, it seems that at least on the societal level (if not on a philosophical one), we are still prescribing skepticism toward certainty rather than describing it as our existing reality or portraying it as our lived experience. In fact, the borderlines outlining different social categories based on criteria such as gender, age and race, are surprisingly still among the most problematic realities of our time. Sorting people according to what are their “common features,” has resulted not only in extreme superficiality but also in hierarchizing of relations between the groups.

Borderline exhibition also adopts the literary theory of intertextuality to explore the eclectic, multi-coded nature of phenomena. As Julia Kristeva the Blugarian-French literary critic defines it, intertextuality means each text is a mosaic of quotations; any text is the absorption and transformation of another. While intertextuality has been mainly used for discussing the notions of influence and inspiration in art and literature and consequently to address issues of authorship and plagiarism in these fields, Borderline exhibition takes concepts such as influence to address a whole different issue. In fact, the curatorial framework of the exhibition, approaches intertextuality as a philosophical paradigm shift that undermines the borders between texts and exposes their eclectic, polyphonic nature. Thus, intertextuality, in its very core, delves into the structural relationships between texts and shows how each text is inherently made up of other texts, or in other words, how each text opens to “infinite play of relationships with other texts or semiosis.” Consequently, there is a close relationship between intertextuality as a literal theory and Postmodernism and the Borderline exhibition particularly aims to scrutinize the postmodern aspects of intertextuality such as: relationality, eclecticism, and interconnectedness of texts, not in the context of literature, but as they apply to arts in terms of form, aesthetics, material, and concept.

The exhibition contains three different and at the same time overlapping sub-themes, namely: identity, medium, and space. While we do not claim absolute comprehensiveness with these sub-themes, we believe these are among the most critical areas, on both artistic and societal levels, in which the function of borderlines has resulted in exclusivity, othering, and hierarchization. Works have been selected for this exhibition with an aim to raise questions about the “either/or,” black /white, and in one-word dichotomic approaches. The installation of the exhibition itself is a metaphorical representation of the fragility, temporariness, constructedness, and arbitrariness of the borders between the categories it defines. Therefore, instead of installing the pieces in a traditional curatorial order – which means placing each piece in the space allocated to its respective sub-theme- the pieces literally break into adjacent spaces, this irony is supposed to encourage viewers to question the certainty of thematic borders. This layout also creates a visual equivalent to the interconnectedness of territories and uncertainty of the borderlines that define them. Moreover, by “breaking” the homogeneity of the categories that we have already defined for the viewers and disrupting their specified spots, we address the inherent, uncertain and eclectic nature of the conceptual spaces of the exhibition. In fact, the presence of a piece within the thematic section to which it did not originally “belong” is a visual allegory to the situation that Gerard Genet, the French literary theorist, defines as “the actual presence of one text within another.”